wishing well

I write at the shiny new downtown Starbucks frequently gazing through glass panel windows while lone shoeless banker gathers deposits from historic towering fountain each monday morning after weekenders and marketers and late-night frolickers have departed town square

up the way two associates dicker over day trading shots of jack daniel’s and evan williams for like a dollar and a quarter a shot

treasure hunters in the median

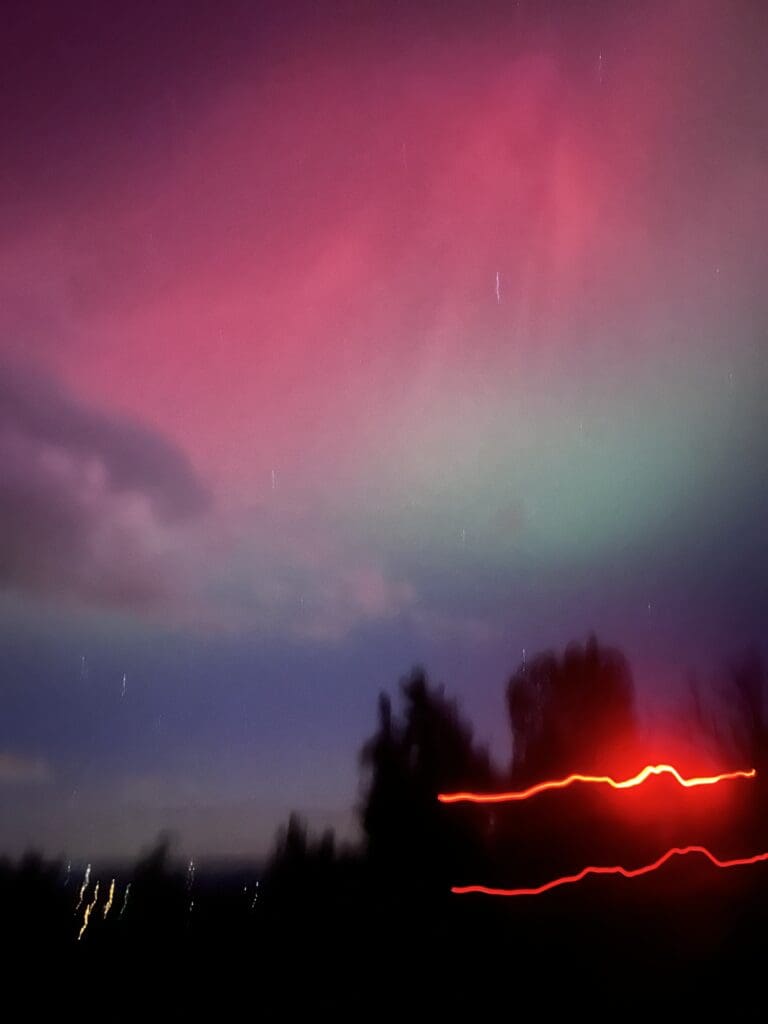

neon multiverse

cory hollingsworth said “the people are the star” and now we’re cooking

I’ve been trying to needle down into the heartbeat of the magic city

I remember – do you remember –

marching into the packed market building as a child

to get a burger in the square hamburger topped

with lettuce tomato pickles mustard and ketchup and a soda on the side

because that’s how I still like my burgers so that’s how I know it’s true

taking a seat at those rough old wooden tables with benches

undersides sticky with years of fingerprints and chewed-up gum

and who-knows what-else and then as a starry-eyed little child

I would look up high at the expansive market building ceiling way up high

before the renovation before the renovation and I looked up there

at that seventies or eighties era ceiling and I saw the most beautiful galaxy

of neon stars and swirls that i had ever seen – a multiverse in our little big city

do you hear the woods rumbling?

sit awhile with me I said

whisper in my ear the causes

that compel you to lit your voice

anthems that set our hills a-sway

our city is not a quiet city

our city is a troublesome you say

filled with changemakers troublemakers

torchbearers lighting the way

setting the woods aflame with rumbles

of vision invention divination

rods crossing wildly proclaiming

do not delay

The 91/61 Split 3

I’ve learned that there are families who choose to be one-car families. They choose to take a road that seems to be more difficult to me but seems to be just-right to them. Partners take turns with the car. One might bike or walk or ride the bus to get where they need or want to go, even with children in tow. They even come to accept help from their friends or family, sometimes.

The Garland family is one of those families. I rode the bus with Andrea on Earth Day. She grew up in Colombia, in a culture that promoted a freedom of mobility. She walked everywhere as a child, she said. She went to college in Bogota, was influenced by Enrique Peñalosa’s transformation of the transit system. Somewhere along the line, Peñalosa said, “An advanced city is not one where the poor own a car, but one where the rich use public transport.”

Andrea lives on the 61.

When Andrea married her spouse, he had a car. They didn’t see the need for a second one, she said. It just stayed that way and became a lifestyle for them. They would take their children to preschool at the Jefferson Center, riding bikes with cargo carriers across the Wasena Bridge. They walked places. They communicated with each other when they needed the car to drive further away, like to a dentist appointment, she said.

They are committed to sharing a car and using alternative transportation because they believe in it. They situate their lives so that they can live their values. They’ve chosen their house, their jobs, their everything based around the amenities in the neighborhoods – are they walkable? Bikeable? Is the home near a bus line? Do they have freedom of mobility?

Andrea lives on the 61. I did too. I grew up right on the 61. I only had to dash out my door and down my front yard of a hill to catch the bus and still I was afraid I would miss it.

My granny lived on Grandin. We’d call that the 65 but I’d call it home.

The 91/61 Split 1

Two weeks on the bus and I’ve learned that I have a lot to learn. It’s a humbling experience. I’ve had to trust that the bus will arrive when the bus schedule says that the bus will arrive and that I don’t have to be (so) self-sufficient. Cars make us self-sufficient.

I am riding the bus because I can.

My first day on the bus, I met a woman. She was sitting in the rear of the Third Street to Tanglewood 51 with her small child. She stays on the 91, she said. She rides the bus everyday, she said. She had been to Valley View and back, and then on to Tanglewood. She would be riding the loop back downtown again to meet her mother. There had been a lapse in communication, she said. She stays on the 91.

She stays on the 91. “What does that mean?” I asked.

The 91 is the route that ends in Salem. She lives on the bus line. Since she rides the bus everyday, she must live on the bus line. Her options for housing are limited to those on the bus line. She stays on the 91.

The 91 goes from the Third Street Station through northwest to Melrose. It passes the site of the future Melrose Plaza and the Melrose library before traveling through downtown Salem, providing access to lots of restaurants, a pharmacy, parks and the farmers market. It continues on to Walmart for sundries. A spur shoots off Apperson past Integer and on towards Thunder Valley. That’s what the map says.

She chose to stay on a bus line that has nearly everything she needs contained on it. She does not stay on it. I’ve seen her again. She travels.

The 91/61 Split 2

I rode the 91 today, where the woman-I-met-on-the-bus on the first day I rode the bus stays when she isn’t riding the bus.

The 91 today is a community bus, a chatty sort of bus, a how-you-doin’ bus, a let’s-catch-up kind of bus. The men in hats sit side by side wearing red-and-orange plaid and blue-and white-and-pintucked-gray stripes and pristine-matching-pants to tip-top-shirts in a fashionable sort of way, leaning on canes and rocking, always rocking with the herky-jerky tide of the bus.

The men, they are of the older sort, the talkative sort, the friendly and good-to-see-you sort. They remind me of the front-porch-grandpa always sipping some cold-sweet-tea and inviting the neighborhood cats in for a story. And still we roll.

We roll past one short-posted bus stop with a graying broken stool leaning lopped against metal sign post, just leaning there like an old tired woman resting her worn graying back. We roll past refinished basketball courts and retaining walls holding up empty lots of green green grass and dandelion wishes. We roll past lots for sale and the same junked out car lots we see all over the city, but fewer of them somehow.

Mostly though we roll past red painted porches and new wooden fences and new wooden topped decks and brightly blossoming flowers and pretty pink paint like a maiden’s manicure on the first prom night of summer.